Birds of a Feather: Little Rock’s Chester Nests

by Katherine W. Stewart, Preserve Arkansas Membership and Communications Coordinator

June 14, 2024

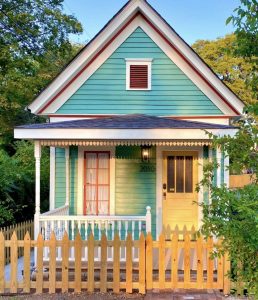

The Chester Nests are a cluster of brightly colored cottages that hug the corner of Chester St. and Charles Bussey Ave. in Little Rock’s Dunbar School Neighborhood Historic District. Restored over the last two years by Angela and Bobby Mathews, along with Angela’s mother, Lynn Boyd, the Nests — impossible to miss with their exuberant paint palettes, like the plumage of tropical birds — currently serve as short-term rentals. The project was awarded Preserve Arkansas’s 2023 Preservation Award for Outstanding Service in Neighborhood Preservation and is just the latest in a campaign to restore vibrancy to some of Little Rock’s oldest neighborhoods.

The passion for preservation is a family affair with roots that go back half a century.

“It’s in your blood; I started doing this in 1974,” Lynn says, smiling at daughter Angela.

First there was a house in Hillcrest, Angela explains, where they started DIYing — though they both insist that was primarily cosmetic work. Then Lynn bought another house, which they also updated. Then Angela and Bobby got married and moved to the Central High neighborhood, where they planned to buy a huge house that they would all live in and rehab together.

“Tony Curtis showed us this house in Central High, and we basically fell in love with the staircase,” Angela says. “The rest of the house was a mess.”

“And the stained-glass window!” Lynn interjects.

“The stained-glass window, the staircase, and it still had all the original trim — that was not painted,” Angela emphasizes.

That was their largest project to date and the first in which they utilized historic tax credits to assist with the financing. It’s also where they met many of the contractors and craftspeople that they would continue to work with on future projects — including the Chester Nests.

“We decided that if we could do one house, why not do three?” Angela says.

The shotgun cottage — the first to be restored, now named the Hummingbird — popped up on the MLS, and Angela had always wanted to do a tiny house. Bobby was traveling for work at the time, but Angela and Lynn went to look at it.

“I fell in love with the shotgun house … and then we were under contract before Bobby got back,” Angela says, chuckling. “I feel like it takes a special type of person to walk in and think, Oh, these are awesome, because there were holes in the floor, and the whole house was tilted.”

Their intent was to acquire the shotgun cottage along with the neighboring duplex on Chester St. and a cottage around the corner on Charles Bussey Ave., then use state and federal historic rehabilitation tax credits to restore all three, creating what Angela refers to as a “tiny house commune” of Airbnb properties; the rental income combined with the tax credits would make the project financially feasible.

But first, they had to actually acquire the properties — which is often easier said than done, especially when there are complicated ownership issues. Fortunately, Angela is a real-estate attorney with plenty of title experience, so they were able to work with the title company, insurers, and the family to reach an agreement.

“How we end up with a lot of heir property issues is that people assume if you have a will, you have the paper,” Angela explains. “But the will has to be probated, and if you don’t do it within a certain amount of time, it’s like not having a will.”

“This is why I strongly encourage beneficiary deeds,” she continues. “With the deed, you don’t have to worry about probate; it just goes to wherever you say it goes to.”

Having taken possession of all three dwellings, it was time to get to work, which included not just a lot of the cosmetic work that the trio had become accustomed to, but repairing or replacing roofs, floors, walls, windows, foundations, and interior and exterior features in various states of degradation.

Angela can’t stress enough how important it is to have a contractor who wants and knows how to work on historic properties.

“Not every contractor wants to, or will, or can work on old houses,” she says. “It takes a special contractor, because nothing is going to be square; nothing is going to be level.”

Between their years of DIY experience and a small army of subcontractors, plumbers, electricians, craftspeople, and helpful friends, it took them two years from start to finish to get the first three Nests, plus an additional one acquired after work began, finished and ready to rent. And that includes facing a major and unanticipated snag from the city.

“The city wasn’t regulating short-term rentals when we started this project, and then in the middle of it, they started talking about passing short-term rental regulations, and there was a whole rezoning process,” explains Angela.

Knowing that their project wouldn’t be feasible without the rental component to help recoup their investment in the restoration, they tried not to panic. They went to countless board and planning commission meetings trying to convince the city that short-term rentals could be a good tool for development.

“It ended up being okay, granted, but it was a very costly, very long process getting approved by the city,” says Angela.

The hard work has paid off: The Chester Nests maintain a high occupancy rate (with the shotgun hovering near 100%) and have earned Airbnb’s “Guest Favorite” and “Top 1%” badges. Even without setting foot inside, it’s easy to see why. The cheerful exteriors of the Hummingbird, Heron/Mockingbird, Goldfinch, and Robin are intended to make people happy.

Inside, the bird theme — the idea for which Angela credits to local preservationist Paul Dodds — continues with modern bird-motif wallpaper that forms the basis of the color palette for each house. And while each is different, they’re complementary and stand together as a cohesive whole.

“The neighborhood needed something to make people smile, to give them hope again,” Angela says. “I channeled the whole New Orleans colorful vibe, and I think for the most part, the neighbors have been happy with our choices.”

Indeed: The owner of the house next door to the Goldfinch was so pleased by their work that he sold them his family home, saying he wanted them to transform his house, too. That will be their next project, followed by the Funk House, a large pale-red house with a stunning Palladian window that sits on a hill at the other end of the block.

“I looked at Angela and said, ‘They’re going to tear out that window,’” Lynn says. “I said, ‘Well, we’ll just have to buy it.’”

When asked if they had any advice for those wishing to take on a restoration project, Angela and Lynn are unanimous in their suggestions: Talk to other old house people, learn as much as you can on YouTube, be patient, and look into tax credits.

“And don’t rip out your original windows.”

Questions or comments about this article? Reach out to Katherine W. Stewart at kstewart@preservearkansas.org.